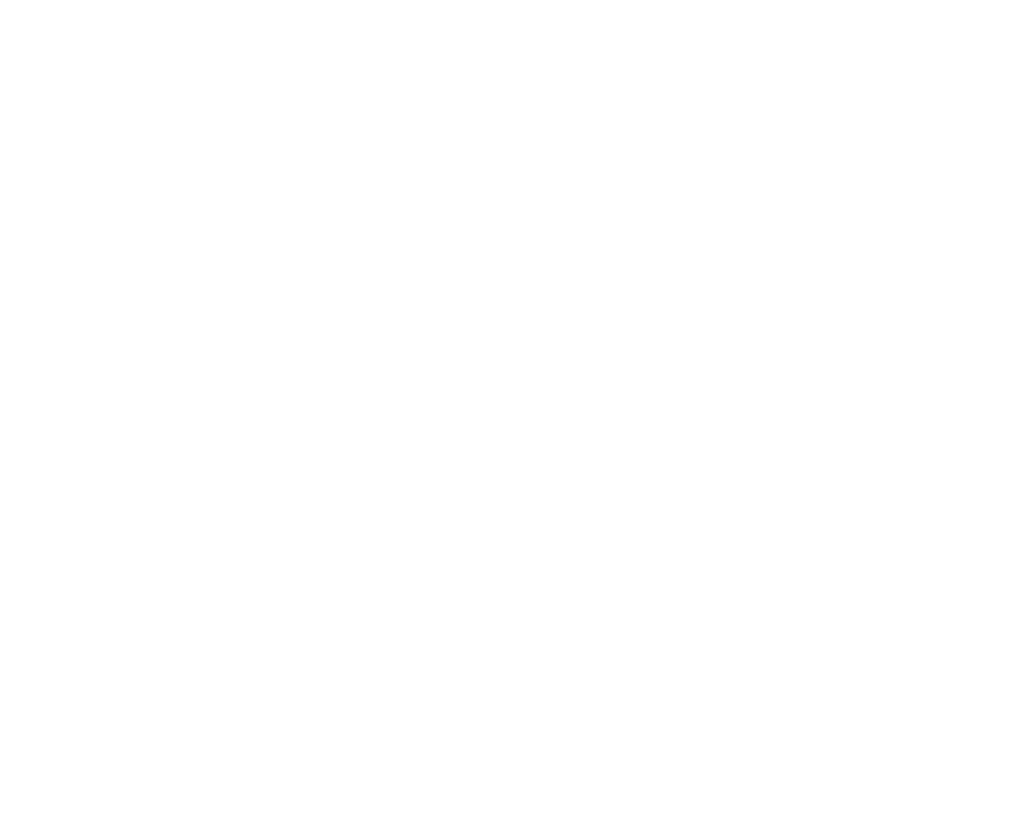

It’s so appropriate that our epic, 3,000-plus-mile, cross-country journey should begin in Liberty Canyon—the site of the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing. The shrill grind and clank of trucks moving earth is loud, crazy music: Construction of California’s first urban wildlife crossing—the world’s largest––is underway!

Photo: Sharon Guynup/Big Cat Voices

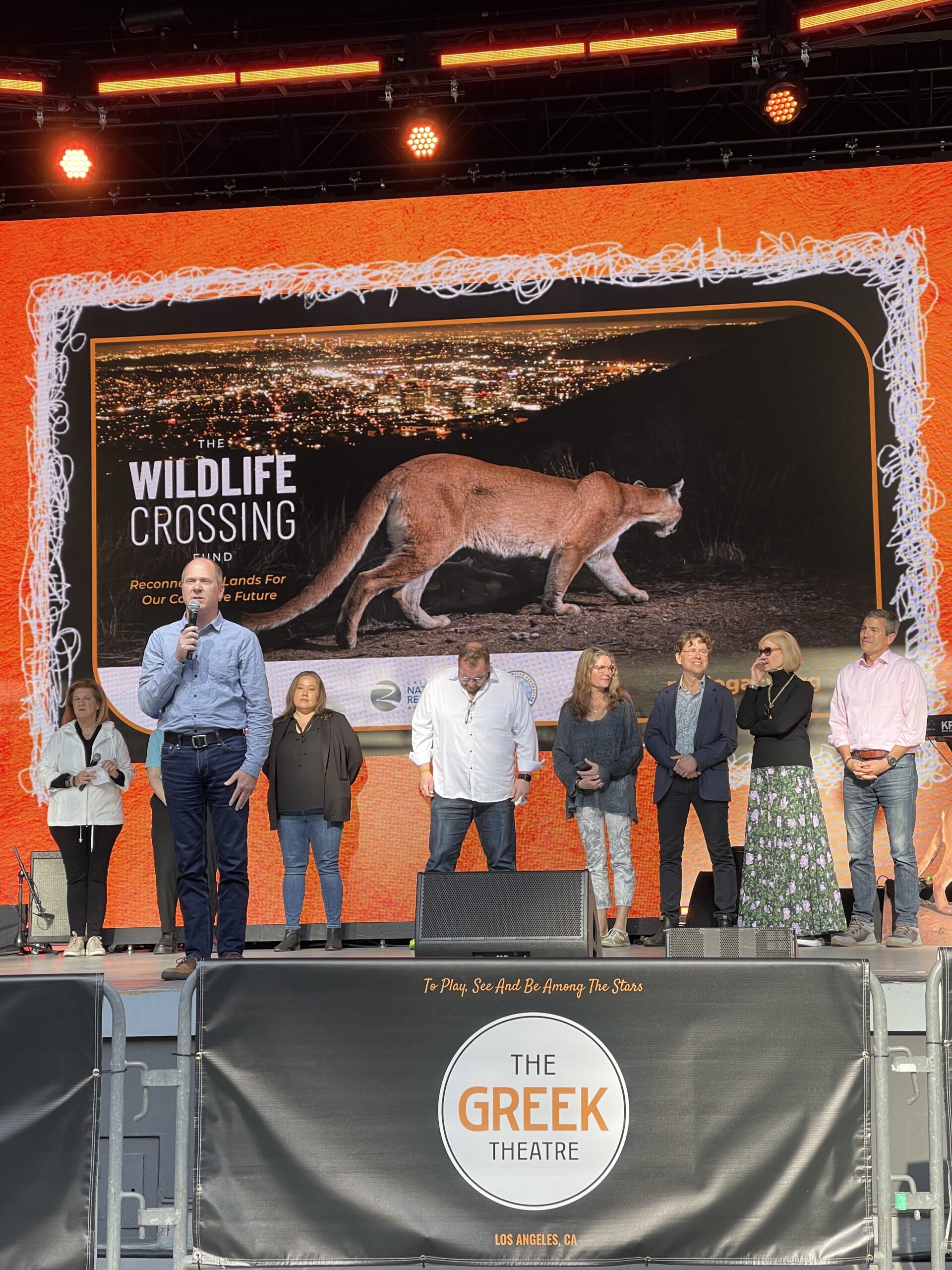

We launched with a press conference across from the construction site.

Photo: Steve Winter/National Geographic/Big Cat Voices

Five of us are driving from Los Angeles to the Florida Everglades to explore similar projects that are creating safe passage for animals. It’s the first at least six road trips for the “Wildlife Crossings Across America” project, the brainchild of Beth Pratt, who heads the National Wildlife Federation’s California operations. We’re also riding with Renee Callahan and Marta Brocki, experts from Animal Road Crossing, or ARC—a nonprofit that helps reconnect landscapes and wildlife habitat. Photographer Steve Winter and I will document and report along the way.

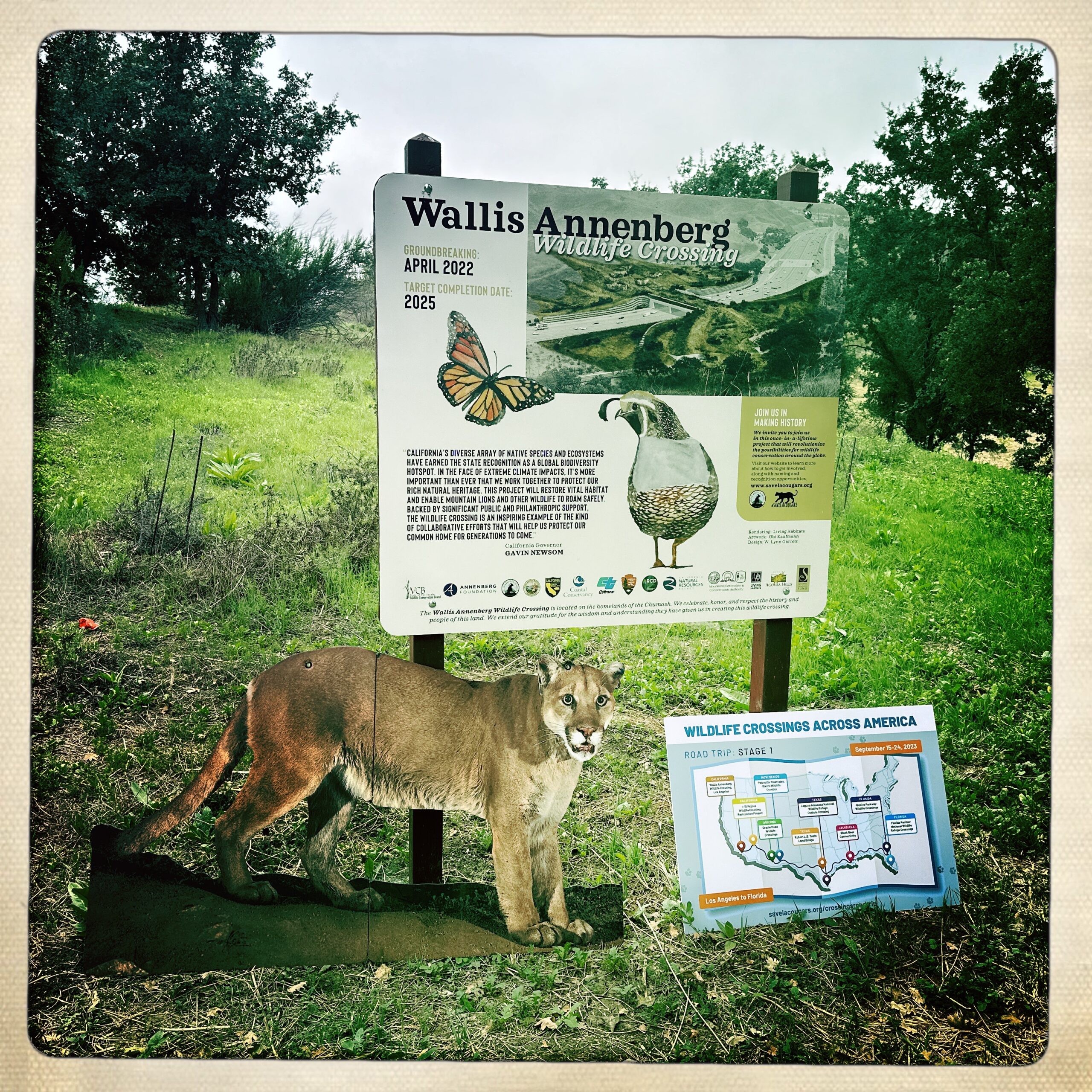

But this is a journey that actually began a decade ago. In October 2013, Steve’s picture of a young male cougar was published on the cover of The Los Angeles Times. The cat, dubbed P-22 (Puma number 22) had miraculously made it across two of California’s busiest freeways as he wandered in search of his own territory—which he needed to avoid battling over turf with another cat. He landed in the unlikeliest of places: L.A.’s Griffith Park, which is visited by 24 million people a year.

Photos: Steve Winter/National Geographic/Big Cat Voices

With that photo, Angelinos realized that they lived beside a wild big cat. Millions fell in love with P-22. “He became a celebrity in the land of celebrities,” Steve says––and he started a movement. Urban wildlife was added to the L.A. public school curriculum. L.A. Declared October 22 “P-22 Day.” The cat has a permanent exhibit at the L.A. Natural History Museum.

But Beth Pratt had a dream: connecting some of the best cougar habitat in the region, which is bisected by the 101 Freeway. She carried around a full-sized cutout of Steve’s P-22 photo for eight years, she brought together all the players needed to make it a reality, raised $90 million from public and private sources––and the overpass broke ground in April 2022.

Photo: Steve Winter/National Geographic/Big Cat Voices

Photos: Sharon Guynup/Big Cat Voices

Beth made a commitment to “her” beloved cat that she would continue to reconnect cougar habitat across California, but she dreamed bigger. Her next initiative was announced at the memorial: the Wildlife Crossing Fund. Beth plans to raise half a billion dollars to build wildlife underpasses and overpasses nationwide. The goal: to protect both animals and people. Collisions kill one- to two-million large animals each year and cause some 200 human fatalities, at a cost of $10 billion.

For wildlife, it’s the eleventh hour. Amidst precipitous wildlife declines—so widespread and severe it’s been dubbed “the Sixth Extinction,” current conservation efforts are clearly not working.

With 334 million people in the U.S., the human footprint is everywhere. For many species, loss of habitat is the greatest threat. Because we have so vastly altered the natural world, wildlife is now trapped within patchwork fragments of habitat. More than 4 million miles of roads fracture habitat nationwide. Even pristine landscapes are sliced by virtually impassable roadways.

But animals must move in seasonal migrations. They must roam to find food, water, nesting or den sites—and an unrelated mate. Isolated populations become inbred, which may begin an often-inexorable march towards extinction. And with rapidly changing climate, the inability to flee may prove deadly. And extreme heat, drought, floods, and wildfire are making some protected areas inhospitable to the species they were created to shelter.

Experts agree that saving wildlife now demands 21st-century solutions—and a new, broader conservation paradigm. The only way to ensure long-term survival for wildlife is through landscape-scale solutions: specifically, connecting, reconnecting, restoring and rewilding ecosystems. This not only saves wildlife; increasing habitat also stores carbon, fighting climate change. With growing public support and government funding, it’s a strategy whose time has come.

The team, from left: Renee Callahan, Beth Pratt, Sharon Guynup, Steve Winter and Marta Brock

Photo Courtesy Sarah Arnoff / Red Rock Films