Photos: Steve Winter / Big Cat Voices

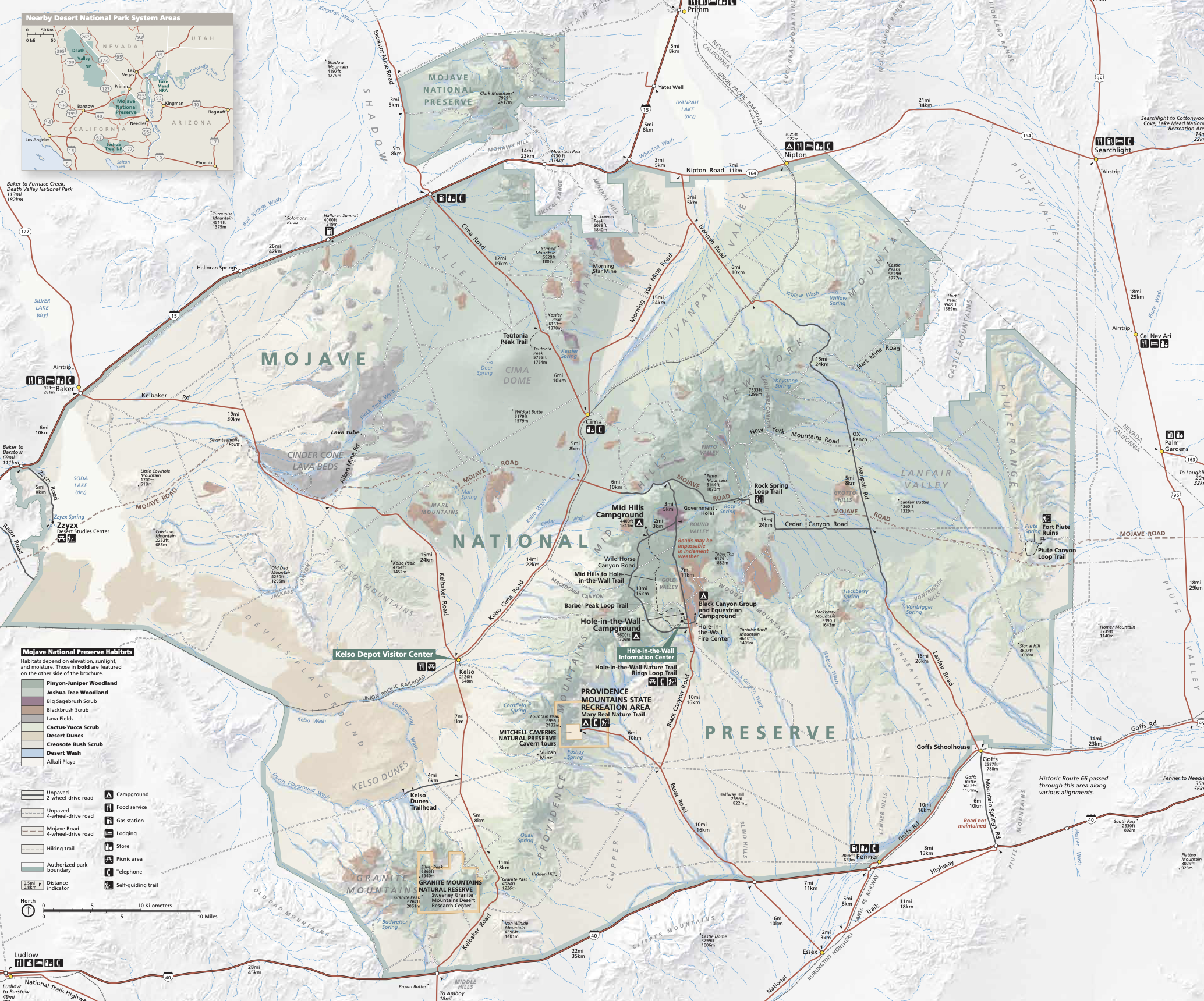

The mercury hit 106 by the time we pulled off “the Mohave Freeway”––I-15––at Exit 239: Zzyzx Road. (A community of the same name, Zzyzx, was named in 1944 by Curtis Howe Springer: he wanted it to be last word in the English Language.) We parked in a barren clearing where Neal Darby waited for us.

As part of his introduction, he told us that in his work as a biologist for the National Park Service, he’s spent decades studying this harsh, rocky landscape.

This is prime habitat for hundreds of species, some endangered. Bighorn sheep, burrowing owls, mountain lions, bobcats, foxes, snakes, roadrunners, golden eagles, Gila monsters, and jack rabbits are just a few of the hundreds of species that move between the lowland and the mountain “sky islands” that offer entirely different habitat.

For years, he says, Interstate 15 has been a barrier that’s fragmented, the habitat. “Wildlife has been able to get across, but it’s a huge, huge risk. You get a lot of roadkill. A lot of vehicle strikes.”

But then came a plan for a “bullet train” from downtown Los Angeles to Las Vegas that will blast along at 200 miles per hour. In California, 135 miles of track will run down the middle of I-15, in the median, sealed off by cement barriers and chain link fences. “It will completely sever the ability for animals to move across the freeway.” The only practical solution was a bridge. So this is now the site of a wildlife overpass-to-be: the project will break ground next spring.

It’s just one of various strategies to protect the Mohave Desert’s wild inhabitants, including culverts and fences to keep animals off the road and guide them to safer passage.

We crossed a parched arroyo and Neal led us to a vantage point that provided an overview: this desert is surrounded by mountains that rise to the west, east and north, but I-15 prevents crossing between them. Beyond, out of our view, there’s another serious barrier: I-40.

Collisions with deer, elk and other large four-leggeds get attention, for good reason. Renee Callahan, who heads ARC Solutions, shared some shocking statistics. Vehicle collisions kill one- to two-million large animals each year. These crashes cause 200 human fatalities and cost some $10 billion in damages—which makes mitigation critical for both animals and people.

But “the little guys” are also in danger, Beth notes. “We just don’t notice it as much because unlike the big animals, they don’t harm our cars and we may not see them lying on the side of the road.”

Photo Courtesy National Park Service

Photo Courtesy National Park Service

For tortoises, culverts tunneled beneath roadways work well—and lizards, small mammals, even insects also pass through. But intensifying downpours flood and clog these passageways—so clearing them is critical. These torrents also rip out guide fences.

The region is seeing growing impacts from changing climate. “Heat waves are more intense, Neil says. “We’re getting more longer, prolonged, intense droughts. “Rain…is less frequent. But [storms] are more intense.”

With extreme weather, animals’ ability to safely move into new areas may determine life or death. Likewise, heat, drought, flood and wildfire are making some protected areas inhospitable, forcing animals to shift habitat: climbing higher, into cooler altitudes; settling into new territory after a fire; or relocating in search of food or water. Desert tortoises are one species on the move: they are moving up into altitudes up to 4,000 feet.

But here, animals will be getting the help they need. This is just one of three overpasses planned for I-15 in California.

***

We drove into the night, landing at a hotel in Phoenix at 10:30. It was a 545-mile day.